Home![]() books

books

![]() ecology

ecology![]() Latest info

Latest info![]() from space

from space

![]() Encyclopedia

Encyclopedia![]() Animals

Animals![]() Plants

Plants![]() Climat

Climat![]() Research

Research![]() The world beneath Baikal

The world beneath Baikal![]() Geology

Geology![]() Circumbaikal railroad

Circumbaikal railroad![]() Photogallery # 1

Photogallery # 1![]() Photogallery # 2

Photogallery # 2![]() Photogallery # 3

Photogallery # 3![]() Listvyanka

Listvyanka![]() Natives

Natives![]() In German

In German![]() Word of poet

Word of poet![]() Olkhon island

Olkhon island![]() Earthwatch

Earthwatch

![]() Shopping

Shopping![]() Travel agences

Travel agences![]() Guestbook

Guestbook

![]()

The climate of Baikal and the Baikal Territory is unique. The lake's huge

water mass gives it certain features of a seashore climate. Rather significant

are the temperature differences between the Baikal hollow and surrounding

territories of Eastern Siberia. Thus,

in

Kachug the average temperature in December is -27 to -39°C, in Irkutsk -25

to -27°C, on the shores of Baikal - 12 to -27°C. In summer, when it is +25°C

and more in Irkutsk, it is +15 - +18°C on Baikal. This difference diminishes

slightly after the lake freezes, but still remains quite noticeable. Baikal

is often called a museum of climates because of the variations that result

from differences in distance from the lake, the shape of the coastline,

the relief and surface of the shores, the steepness of slopes, their orientations,

etc.

in

Kachug the average temperature in December is -27 to -39°C, in Irkutsk -25

to -27°C, on the shores of Baikal - 12 to -27°C. In summer, when it is +25°C

and more in Irkutsk, it is +15 - +18°C on Baikal. This difference diminishes

slightly after the lake freezes, but still remains quite noticeable. Baikal

is often called a museum of climates because of the variations that result

from differences in distance from the lake, the shape of the coastline,

the relief and surface of the shores, the steepness of slopes, their orientations,

etc.

Collecton of the articles in Russian

The year's seasons are a bit displaced on Baikal. Spring sets in here a month later than in the Baikal Territory itself, so the warmest month is not July but August, and it's rather warm in September, too. There is a lot of sunshine on Baikal, much more than on Riga's seacoast and even in the famous health resorts of the south. On Baikal, in Goloustnoye, the annual amount of sunshine is 2,583 hours, while in Pyatigorsk it is only 2,007 hours.

The amount of precipitation also varies at different parts of the lake. The greatest amoutn falls near the southern end of Lake Baikal. Warm masses of air from the southwest abruptly cool over the lake's surface, yielding an average annual precipitation of 495 millimetres.

At the northern end of the lake precipitation is much less abundant, and in the Dagary Region it amounts to only 258 millimetres. Most precipitation ffalls during the warm seasons.

The wind regime of the lake is also very interesting. Besides the general synoptical situation and the features of local air mass circulation, the directions and the speeds of the air currents are influenced by the location of the mountain ranges.

Baikal

is a stormy lake; in autumn there can be 18 stormy days a month, while there

are only three on the Black Sea, and four on the Azov Sea. The Baikal's

winds blow in various directions. The longitudinal winds - the verkhovik

(coming from above) and the kultuk blow along the Baikal hollow.

Verhovik blows from the north of Baikal, mostly in autumn. With this

wind, the weather may be bright and sunny, with blue sky and green and dark-blue

waves rimmed with white caps. When the verkhovik gets stronger, Baikal

turns black, with white crests of waves upheaving. This wind blows up great

waves in the southern part of the lake.

Baikal

is a stormy lake; in autumn there can be 18 stormy days a month, while there

are only three on the Black Sea, and four on the Azov Sea. The Baikal's

winds blow in various directions. The longitudinal winds - the verkhovik

(coming from above) and the kultuk blow along the Baikal hollow.

Verhovik blows from the north of Baikal, mostly in autumn. With this

wind, the weather may be bright and sunny, with blue sky and green and dark-blue

waves rimmed with white caps. When the verkhovik gets stronger, Baikal

turns black, with white crests of waves upheaving. This wind blows up great

waves in the southern part of the lake.

When the kultuk is blowing, the weather gets dull, with low clouds, and Baikal becomes leaden-grey, gloomy and stern. In the north of Baikal this wind drives waves of three metres and more.

The barguzin, glorified in a folk song, blows from the valley of the Barguzin Rive, across the lake. It was this wind that helped the legendary swimmer cross Baikal in an omul barrel.

But the strongest, most threatening and dangerous of Baikal's winds that blows northwest, is the gornaya (mountain-bred). One of its variety, the sarma, blows from the river valley of the same name, where it reaches a hurricane's strength, up to 40 metres per second and more.

A very peculiar feature of this wind is its suddenness. Nothing seems to betoken the beginning of the gornaya. The weather may be quiet and warm, but the atmospheric pressure drops sharply, ranges of stratus and cumulus clouds are appear from above the mountains, turning dark gradually, then the first wind gusts come flying up, tearing up ripples, and all this rushes to the eastern shore of Baikal, where the waves, of 4-6 metres high, break themselves against the coastal cliffs. In 1902, during a spell of the gornaya in the Maloye Sea near Semisosenny (Seven Pines) ulus, the ship Potapov perished with its 200 passengers. Baikal is not to be trifled with, and the history of navigation on Baikal could recount quite a few sad stories.

I. Stakheyev, in his book Behind Baikal and on the Arhur River (S.-Pb, 1859) wrote such lines: 'Woe is the wanderer who's been thrown by fate into the wave arms on a frail Baikal boat; this boat is drifting over the sacred sea, swinging from side to side, from prow to stem, the water and ice blocks gushing into it. The boat gets iced up and in this shape, sometimes during 2-3 weeks running, it floats on Baikal from one end to another; first it is driven by wind to the shore of Kadilnaya Bay, so that the wanderer could enjoy the high mountains and cliffs; then it is swiftly carried away to the other side, and, knocked about by its caprices, the boat is placed opposite the Ambassador Monastery. The wanderer crosses himself from afar at the Orthodox Church, and no sooner can he have worked up the prayer than the wind catches up the boat and drifts it somewhere to the other side.'

In our days all ships and motorboats are equipped with radiostations, so they are duly warned about coming storms and seek shelter at bays.

The old-timers might name dozens of varieties of another wind - the shelonnik, a south-caster. The nature of this wind is often explained by intrusion of cold air masses coming from the east over the mountain ranges. The gust of the shelonnik will not always reach the western shore, yet, when Baikal seems cool, there arise steep waves that break in full force against the shores. Then, with myriads of splashes, they fall back into the sea, leaving ice spills of whimsical shapes in late autumn and early winter.

On Baikal, there are breezes resulting from pressure differences over the land and the water surface. In autumn and before the freeze-up, they are almost steady and blow from the land towards the sea. In various parts of Baikal they are called differently: the kholoda, the ayaya, the kharakhaikha, the khivus, etc.

Fogs are frequent on the lake, too. In early summer the land is well warmed, while the lake's surface is still cold. Because of the warm air brought up to Baikal's cold surface, condensation occurs, giving rise to fogs. In autumn, before freeze-up, the water remains warm for long. The evaporations cool down, producing the so-called frosty fog.

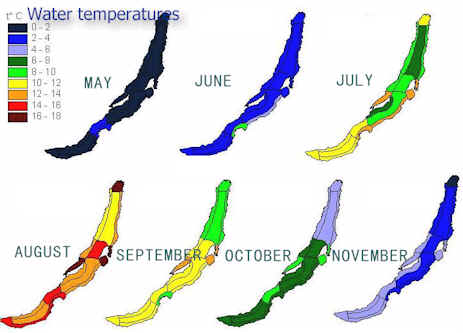

The majority of travellers are anxious to visit Baikal in warm seasons.

In summer Baikal is beautiful; the satiny smoothness of the water stretches

far beyond the horizon. However, the water can hardly be called warm - its

normal maximum temperature is +12°C, and rarely it reaches+16°C. The upper

50 metres of water is most intensively warmed up and cooled down; from +12°C

in August up to 0°C in February.

In

January, when the water of Baikal is cold and is mixed constantly by wind

waves, the overcooled water provokes formation of intro-water grained ice

with crystals having the shapes of dice, needles, lentils, peas, and ranging

in size from 1-2 to 10-20 millimetres in diameter. The temperature of water

when this occurs is -0.2°C - -0.4°C. This results in the rustle mass, mostly

in the wave-surf zone, near the shore. When the rustle mass freezes, it

forms turbid ice with a distinct grain structure.

In

January, when the water of Baikal is cold and is mixed constantly by wind

waves, the overcooled water provokes formation of intro-water grained ice

with crystals having the shapes of dice, needles, lentils, peas, and ranging

in size from 1-2 to 10-20 millimetres in diameter. The temperature of water

when this occurs is -0.2°C - -0.4°C. This results in the rustle mass, mostly

in the wave-surf zone, near the shore. When the rustle mass freezes, it

forms turbid ice with a distinct grain structure.

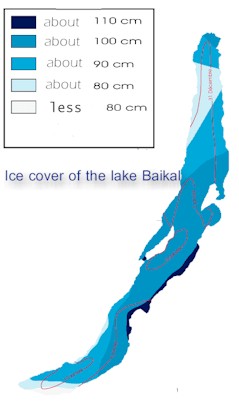

In the second half of January, Baikal is fully covered with ice a metre thick and more. During the Russo- Japanese war, when the ice thickness was more than one and a half metres (the winter of 1904-1905 was severe), the railway track was laid straight over the ice, which made it possible to haul 2,300 carriages and 65 locomotives across the water by horse traction over a period 17 days.

The ice on Baikal is a unique phenomenon. Its vast fields are so transparent that the bottom and its inhabitants can seen at shallow depths. It is somewhat frightening to walk on such an ice, especially at first. If there are no cracks in it, it is not easy to estimate its thickness 'by eye' its thickness. It seems that, under your feet, there is a huge dark-green abyss of water. The Baikal winter ice is rather strong, but daily temperature fluctuations cause intricate patterns of cracks that are called permanent gaping crevasses, some of them several metres wide. Formation of crevasses is accompanied by strong booms, crackles, and other noises.

Nikolai

Spafarii has written: 'The ice lives growing in thickness of a fathom thick

and more, therefore in winter time it is walked upon in sleighs and dog-sledges,

yet it gets rather frightful when the sea, at full rest, falls apart in

halves, thus causing crevices of three fathoms wide or more, and soon all

is brought together again with great noise and thunder, and at the site

there arises a kind of an ice billow; there is great noise and thunder living

under the water as if cannon- a-shooting (those ignorant of are greatly

terrified), particularly between Oikhon Island and Saint Nose Cape where

the deep is great.' When the temperature rises, the ice expands, causing

gaping crevasses to close up, their edges to splinter, and fragments of

ice-floes to pile up in hummocks - vertically heaved-up ice blocks of blue

colour, up to 3 metres high or more. Greater rises of temperature cause

ice masses to crawl ashore, reaching inland up to 10-30 metres.

Nikolai

Spafarii has written: 'The ice lives growing in thickness of a fathom thick

and more, therefore in winter time it is walked upon in sleighs and dog-sledges,

yet it gets rather frightful when the sea, at full rest, falls apart in

halves, thus causing crevices of three fathoms wide or more, and soon all

is brought together again with great noise and thunder, and at the site

there arises a kind of an ice billow; there is great noise and thunder living

under the water as if cannon- a-shooting (those ignorant of are greatly

terrified), particularly between Oikhon Island and Saint Nose Cape where

the deep is great.' When the temperature rises, the ice expands, causing

gaping crevasses to close up, their edges to splinter, and fragments of

ice-floes to pile up in hummocks - vertically heaved-up ice blocks of blue

colour, up to 3 metres high or more. Greater rises of temperature cause

ice masses to crawl ashore, reaching inland up to 10-30 metres.

In March or sometimes late February, steam-up gaps (unfrozen patches of

water which are locally called "springs") form in certain parts

of the lake. There are several causes for their formation. In some cases,

currents raise up the abyssal, warmer water to the ice surface, which

results

in preventing the ice from freezing further and eventually in thawing it.

In other cases the rivers that thaw earlier than the Baikal ice surface,

excavate the ice at their mouths. In yet other instances, isolated areas

of gas release (methane, nitrogen, hydrocarbon) become more active in spring

time, pushing up the abyssal water and accelerating local thawing of the

ice. The sites of steam-up gaps at Kadilnaya Cape, in the Maloye Sea, in

shoals of the Selenga delta, in Chevyrkuysky and Barguzinsky Bays, and in

other areas are rather dangerous for traffic.

results

in preventing the ice from freezing further and eventually in thawing it.

In other cases the rivers that thaw earlier than the Baikal ice surface,

excavate the ice at their mouths. In yet other instances, isolated areas

of gas release (methane, nitrogen, hydrocarbon) become more active in spring

time, pushing up the abyssal water and accelerating local thawing of the

ice. The sites of steam-up gaps at Kadilnaya Cape, in the Maloye Sea, in

shoals of the Selenga delta, in Chevyrkuysky and Barguzinsky Bays, and in

other areas are rather dangerous for traffic.

In April the ice loses its transparency and is destroyed. As local residents say, it 'falls apart into needles.' The moment strong winds start blowing in late April-early May, the ice goes to pieces, sparkling with all rainbow colours. This surprising ice symphony sometimes 'keeps the tune' till June. In the north of Baikal there may be ice still floating in the second half of June. That's why the water in Baikal is colder in June than in December. There are records that describe years in which crystal waves of the Baikal ice would be blocked together by wind and then squeezed out onto the shore. It is truly a grandiose sight! In 1930, at Tankhoy Station, the ice was squeezed out onto the 16-metre long railway, where it buried the station and two freight carriages. In 1960, a similar ice field, driven by wind, moved to Listvyanka village. It lifted and toppled the town's pier, smashed the shipyard office, and drove the ice-breaker Angara onto the shore. Such examples are numerous.

Home![]() Books

Books ![]() Ecology

Ecology![]() Latest

info

Latest

info

![]() from

space

from

space ![]() Encyclopedia

Encyclopedia

![]() Animals

Animals![]() Plants

Plants![]() Climat

Climat![]() Research

Research![]() The world beneath Baikal

The world beneath Baikal![]() Geology

Geology![]() Circumbaikal railroad

Circumbaikal railroad![]() Photogallery # 1

Photogallery # 1![]() Photogallery # 2

Photogallery # 2![]() Photogallery # 3

Photogallery # 3![]() Listvyanka

Listvyanka![]() Natives

Natives![]() In German

In German![]() Word of poet

Word of poet![]() Olkhon island

Olkhon island

![]() Earthwatch

Earthwatch

![]() Shopping

Shopping![]() Travel agences

Travel agences![]() Guestbook

Guestbook

realvideo

![]() Transsiberian

railway.

Transsiberian

railway.![]() Inside

the train at Transsiberian railway,download .mov 468kb

Inside

the train at Transsiberian railway,download .mov 468kb![]() Circumbaikal

railway

Circumbaikal

railway![]() Lake

Baikal beauty

Lake

Baikal beauty![]() Yachts

at Baikal

Yachts

at Baikal![]() Brown

bears at lake Baikal shores in spring

Brown

bears at lake Baikal shores in spring![]() Aqualangist

under Baikal ice

Aqualangist

under Baikal ice![]() At

lake Baikal beneath

At

lake Baikal beneath![]() Baikal

nerpas

Baikal

nerpas![]() History

of Trans-Siberian

railway

History

of Trans-Siberian

railway

![]()

|

|

|